All Eyes on Burry: The Incoming AI Crash

It’s happening again.

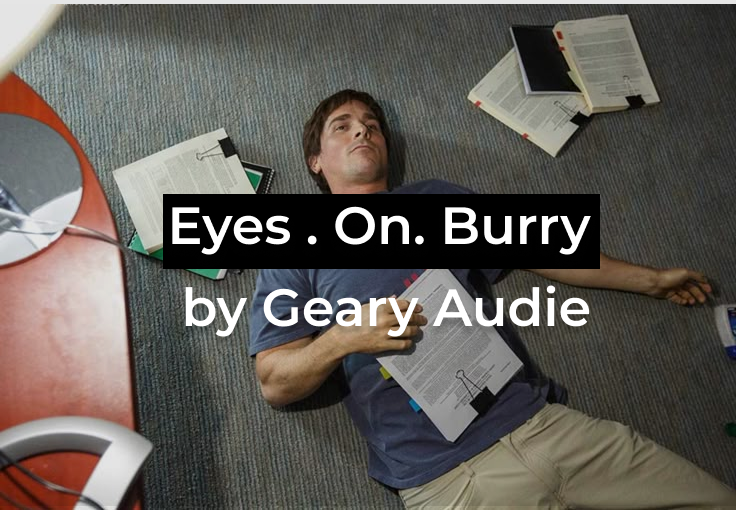

Michael Burry, the investor made famous by The Big Short for predicting the 2008 financial crisis, is once more sounding the alarm. Known just as much for being early as for being right, Burry has been warning loudly about what he believes is a massive AI-driven bubble forming in the U.S. stock market.

Whether the world listens or not may not matter. If he’s right, the outcome will be the same: difficult times ahead for many.

An Economy Propped Up by AI

The dominant growth narrative in the United States today is AI. While precise figures are debated, a disproportionate share of recent U.S. GDP growth is now attributed, directly or indirectly, to AI-related expansion. Markets, capital flows, and policy expectations are increasingly tied to this single theme.

The U.S. economic engine is heavily supported by AI leaders and infrastructure providers such as NVIDIA, Palantir, Google, AMD, and Oracle. Any sharp slowdown, valuation reset, or confidence shock in this sector would not stay contained. Given the United States’ central role in the global economy, the ripple effects would likely be worldwide.

At the same time, the economy has taken on a K-shaped structure. Asset prices and corporate valuations continue to climb, while wages lag behind. Inflation has not disappeared. It has become selective. Costs tied to education, housing, healthcare, and financial assets keep rising, even as income growth stagnates. This form of hidden inflation adds strain and increases systemic fragility.

Why Burry Thinks the AI Bubble Is About to Burst

1. Real Value, Unreal Valuations

Unlike the dot-com era, today’s AI companies are not empty shells. They generate real revenue and, in many cases, enormous profits. That distinction matters.

But valuation still matters.

Many AI-related stocks are priced at levels far above long-term historical norms of the U.S. market. Current valuations assume near-perfect execution, sustained exponential growth, and permanently high margins. History suggests those conditions rarely persist.

One area of growing concern involves GPU depreciation timelines. Several large firms have extended depreciation schedules for data-center GPUs from roughly two to three years to as long as four to six years.

This practice is not illegal and can be justified if hardware remains productive for longer. However, extending depreciation lowers short-term expenses and inflates reported profits. If demand fails to meet expectations, those assumptions quickly become a liability. While not fraud, it is a subtle form of accounting-driven earnings inflation and often a warning sign near market peaks.

2. The Self-Feeding AI Feedback Loop

At the core of the current AI boom is a feedback loop where the same money is effectively reused and multiplied, creating the appearance of explosive growth.

The loop centers around NVIDIA, OpenAI, and Oracle.

NVIDIA has invested directly in OpenAI. OpenAI then commits to large-scale cloud infrastructure deals with Oracle to support its rapidly growing compute needs. To meet those commitments, Oracle purchases massive volumes of NVIDIA GPUs to build new AI data centers.

In effect, the flow is circular. Capital moves from NVIDIA to OpenAI, from OpenAI to Oracle, and from Oracle back to NVIDIA.

Each company reports growth. NVIDIA books record GPU sales. Oracle reports expanding cloud commitments. OpenAI scales compute capacity.

But much of this activity is driven by the same capital circulating within the AI ecosystem, not by entirely new end-user demand.

What sent Oracle’s stock sharply higher was its reported surge in Remaining Performance Obligations, or RPO. RPO represents contracted future revenue. It reflects revenue promised under signed agreements but not yet earned or collected. It is not cash in hand, and it is not guaranteed profit. Markets treated the jump in RPO as proof of durable growth, even though much of that revenue may sit years in the future and depends on continued demand.

This dynamic feeds directly into supply-induced demand.

AI infrastructure is being built first, at massive scale, based on expectations of future usage. Compute is often discounted or subsidized to drive adoption. Usage rises because supply is abundant and cheap, not necessarily because customers are willing to pay full economic prices long term.

As long as capital remains easy, the loop sustains itself. If funding tightens or demand fails to mature into profitable, recurring usage, the entire structure, including chipmakers, cloud providers, and AI labs, faces a synchronized slowdown.

Cassandra Unchained

Burry’s online persona, Cassandra, is telling. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was cursed to speak the truth while never being believed.

History suggests that ignoring uncomfortable warnings comes at a cost.

So the question remains. Is Burry simply early again, or are we witnessing a macro shift where AI permanently rewrites economic rules?

Based on valuation extremes, circular capital flows, accounting adjustments, and widening inequality, one explanation appears far more likely than the other.

All eyes are on Burry, not because he is always right, but because when he is right, the consequences tend to be enormous.